Wow, wow, wow – this is a novel to be in awe of. A thousand pages of incredibly written literary fantasy that keeps you gripped page after page.

It’s an impossible task to summarise the plot! A few things though. It’s set in the nineteenth century. Mr Norrell is an arrogant fuddy-duddy who believes he is the only person who can perform magic properly, and after a successful conjurring in York Minster goes to London and gets the ear of government.

Jonathan Strange is a young upstart who discovers an ability to do magic, becomes Norell’s apprentice but eventually moves on, his arrogance and desire to practice magic at his own pace getting the better of him.

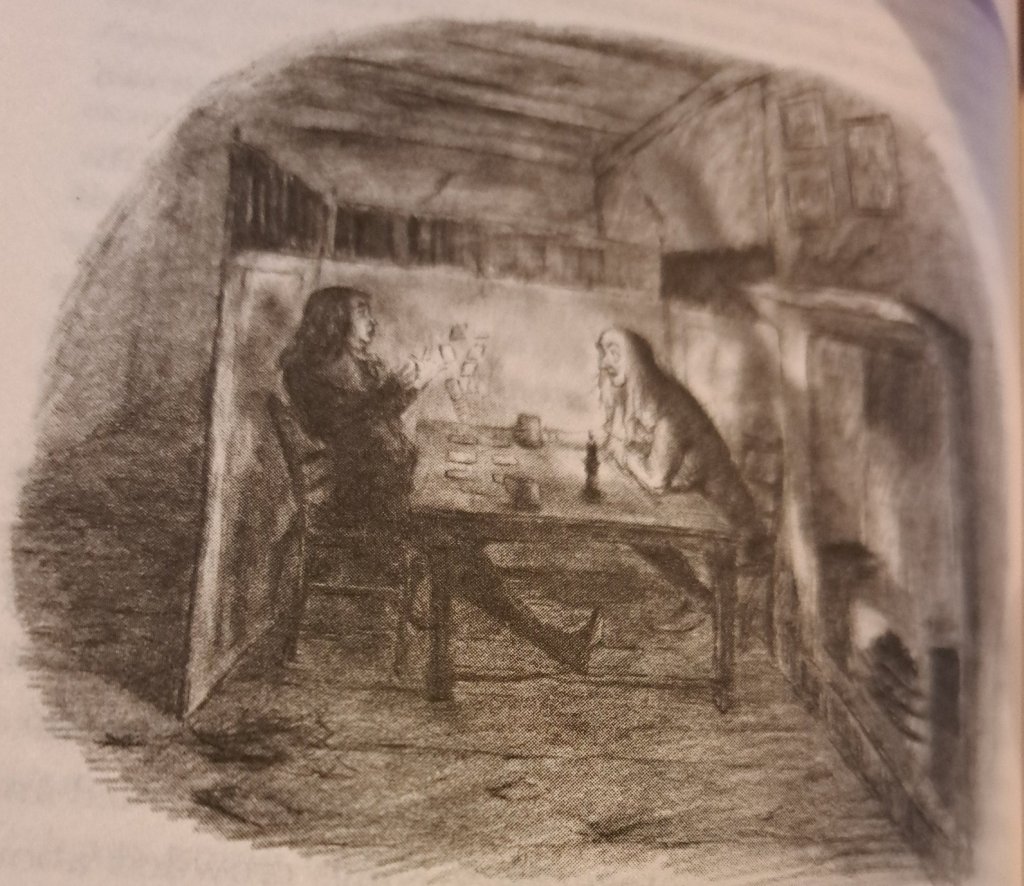

Through the story the pair practice magic of many kinds, often with effects unknown to them. In particular, their magical activities break the barrier between the human and the fairy world, in which a fairy with ‘thistle-down hair’ keeps people enthralled and controlled.

A woman – central to the story – who Norrell brought back from the dead (Lady Pole), Strange’s wife (Arabella) and Lady Pole’s servant (Stephen) all find themselves trapped each evening in this fairy world, but unable to break out or even speak of it during the day, such is the magic of the fairy.

Broken by the eventual death of his wife, Jonathan Strange reaches a point where he conjures up a darkness, a massive column in the centre of Venice, and eventually Strange and Norrell confront the fairy’s magic.

There’s so much more plot to this book – so many nuances and lines of fancy – but this is the heart of the story.

So what to say? A few things.

First, the style: incredible. Think of Charles Dickens if he were writing today in a way that mocks himself. Susanna Clarke write like a knowing Dickens, laughing at the characters and their ridiculous ways of behaving. But at the same time the book is full of footnotes and references, all fictional, to give the sense that this is a historically accurate record.

Then there’s the themes. There are some social themes. In particular, the main characters are men, with the women having only a secondary role, and you can’t help but assume that’s done intentionally, to reflect the ridiculous sexism of the time in which the book’s based.

And there’s a class schism. Many of the main characters are upper class, as you’d expect of that time. But it’s the servants and assistants who guide what they do and often provide the most interest – Stephen, a black servant to the Poles who has more about him than anyone, if only he weren’t trapped in the other world; and Childermass, Norrell’s servant who like Thomas Cromwell in Hilary Mantel’s trilogy, is the political brains behind his boss’s – and his own – success.

And there’s a beautiful battle between the old and the new. Norrell is a stuffy traditionalist who wants to keep things as they are, to maintain his own status. Strange is an innovator, wanting to experiment and try out new magical practice. But actually, in the end, both are are as bad as each other, creating forces they know nothing of, an other-worldly magical force that imprisons many and threatens to take over the human world.

And that’s maybe the great theme of this book: When you dabble in magic you can’t expect there to be no consequences. It’s an ungovernable power and you need to expect something in return. In this case the fairy with the thistle-down hair trapping people in his world and moving to destroy or at least invade the existing one. If you play with fire, expect to get burned.