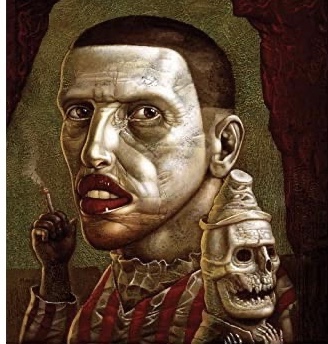

It’s a first-person account of a hypnotist who is putting on a show for a private party. At the centre of his show is his ‘somnambulist’, a woman who he controls completely through hypnosis. The woman, with whom the audience is transfixed – by her beauty as much as by the tricks and contortions he has her do – is entirely under his spell.

The show proceeds as it normally would, ending with a spectacular display of light; a finale. that the narrator feels is entirely under-appreciated by the audience. Rather than the incredible magical acts he provides, they want mere party tricks he complains.

You could be forgiven for thinking the hypnotist is just an illusionist until after the show, whilst the somnambulist circulates to the adoration of the guest, he spies a child watching from the balcony above. As a reader you’re unsure what might happen (this is Thomas Ligotti after all).

But what does happens surprises you – the hypnotist asks the child what do you see when you look at the somnambulist? ‘Yukky’, the child replies, to the hypnotist’s relief. It seems that children, as is often the case in supernatural fiction, can see through the magical facade to the real horror beneath it.

The story ends with the hypnotist, frustrated with the limited imagination and desires of the people at the party, promising to show them the body behind the glamour of a beautiful sleep-walking woman that he’s conjured: the body of a dead woman that he controls; one you assume in a long line of bodies he has repurposed for his own use over the years.

What Ligotti achieves so beautifully in this short story, alongside the power of the plot, is a juxtaposition. On the one hand is a powerful magician, probably a centuries-old supernatural entity himself, who controls the bodies of the dead as if they were puppets.

On the other hand, though, despite this power, he sounds like a sad performer who for some reason earns a living through shows that he feels never get the appreciation they deserve, so narrow are his audiences’ expectations of magic.

At the end, as he says to himself that he he will show them who or what the somnambulist really is, you don’t know if this is the vengeance he’s been waiting to enact for tens or more years, or one more idle threat from a bitter, under-appreciated performer.

* I listened to rather than read this – on the fantastic Pseudod horror podcast, episode 434.